Get the Full Book

This guide is one chapter from Fitness & Nutrition Programming for Beginners. If you enjoy reading it, consider purchasing the full book either as a PDF or paperback. Thanks!

Warm Up: Heat & Movement

The exercise performance benefits of warming up and how to build an effective routine.

Thermodynamic Gains

After a long day spent hunched over a keyboard at the office, you get in your car and navigate through traffic to the gym. A few minutes after arriving, you quickly change clothes and immediately load up the bar with a new one rep squat max. You brace under the bar, lift off, then… die?

Beginning a high-intensity workout without a proper warm up is generally accepted as a bad idea from both a safety and a performance perspective. The previous squat disaster is an extreme example, but the necessity of an effective warm up doesn’t change among various types of exercises.

Whether you’re going for an easy run or setting a new personal best in your favorite lift, taking the time to ready your body before you start will result in a significantly more productive workout. To lift more weight, build more muscle, and lose more fat, we need to warm up.

This chapter defines warm up, covers the benefits of an effective warm up, and discusses how to build your own routine to get the most out of your workouts.

Warm Up Definition & Benefits

A warm up is a brief (10-15 min) and easy exercise routine that occurs before the main workout. This short preparation period readies us for the day’s session by increasing body temperature, boosting blood flow, and priming neuromuscular pathways. The warm up is not a time to treat injuries or perform significant amounts of corrective exercise. Do rehab work on off-days or between sessions.

An effective warm up can be designed in a variety of ways, but all methods should emphasize heat (an internal body temperature increase of at least 1 °C) and movement.

Warm up research primarily focuses on two different styles of warm up, passive and active. A passive warm up raises body temperature by external means (heavy clothing or a hot bath), while an active warm up increases heart rate, blood flow, and heat through exercise. Both of these modalities have been shown to positively affect physical performance and can be accomplished simultaneously.

Some of the most significant combined benefits of active and passive warm ups include –

- Increased ATP turnover rate (faster energy production)

- Increased ATP utilization in individual muscle fibers (greater muscular performance)

- Increased contraction speed (greater muscular power)

- Increased O2 uptake (improved endurance and fat loss)

- Decreased lactate accumulation

- Increased range of motion

- Increased contraction consistency

- Decreased risk of injury

- Decreased joint friction

- Decreased time to reach steady state heart rate

- Increased focus and self-confidence

- Increased motor unit recruitment

In a resistance training setting, these benefits can result in faster muscle growth, improved strength, and increased muscular endurance. For cardio focused sessions, warming up helps us burn more fat, improves our overall conditioning, and allows us to settle into a steady state heart rate sooner. Bigger and stronger muscles, faster and leaner bodies, and a decreased risk of injury. There are too many great things to pass up. We need heat and movement.

Thanks to the thermodynamic products of catabolic reactions, exercise makes us hot and sweaty. This unavoidable result of moderate to high-intensity movement means that we can focus entirely on the style, duration, and intensity of the active warm up and gain the passive benefits. This cause and effect relationship between movement and heat is the foundation of the warm up.

Building The Warm Up

Below is a basic warm up outline built from a mixture of studies that cover heat, exercise intensity, duration, and self-myofascial release.

To quickly summarize the overall concept, we want to wake up the body then practice the movement patterns that will be performed in the upcoming workout. The wake up phase increases our core body temperature through cardio. The practice phase incorporates exercises that mirror the intensity and activities of the day’s session. These two parts are more commonly referred to as general (wake up) and specific (practice).

As shown above, the general section has distinct, separate parts, while the specific half is a mixture of dynamic stretching and plyometric exercises that gradually become the workout. This is designed to maximize transition efficiency and maintain as much heat as possible from the warm up to the workout. From start to finish, this routine takes roughly 10-15 minutes. You’ll be slightly out of breath and a little sweaty when it’s done but full of energy for the work ahead.

Let’s dive a little deeper into the general and specific sections before looking at full warm up examples. How do these warm up components make us better?

Warm Up Structure: General

The general section of the warm up takes roughly 8-10 minutes to complete and consists of self-myofascial release and cardiovascular exercise.

Self-myofascial release (SMR) is the first part of the warm up and can be accomplished using a variety of tools, but we’re going to focus specifically on the foam roller. Studies have shown that pre-exercise foam rolling can acutely increase flexibility, blood flow, and neuromuscular efficiency without causing any of the negative effects associated with static stretching. This means foam rolling boosts our range of motion while maintaining strength, helps deliver more nutrient-carrying blood to muscles, and may lower the motor unit recruitment thresholds for type 2 fibers. All of this can lead to more productive workouts.

Compared to longer SMR sessions after a workout or on recovery days, foam rolling during the warm up should only take a few minutes to complete. Warm up SMR should focus primarily on the antagonistic pairs (opposing muscles in a joint/movement) being worked that day. However, if you aren’t in a rush to get started and want to focus on rolling out your whole body, go for it. Take this time to think about your intent and goals for the day.

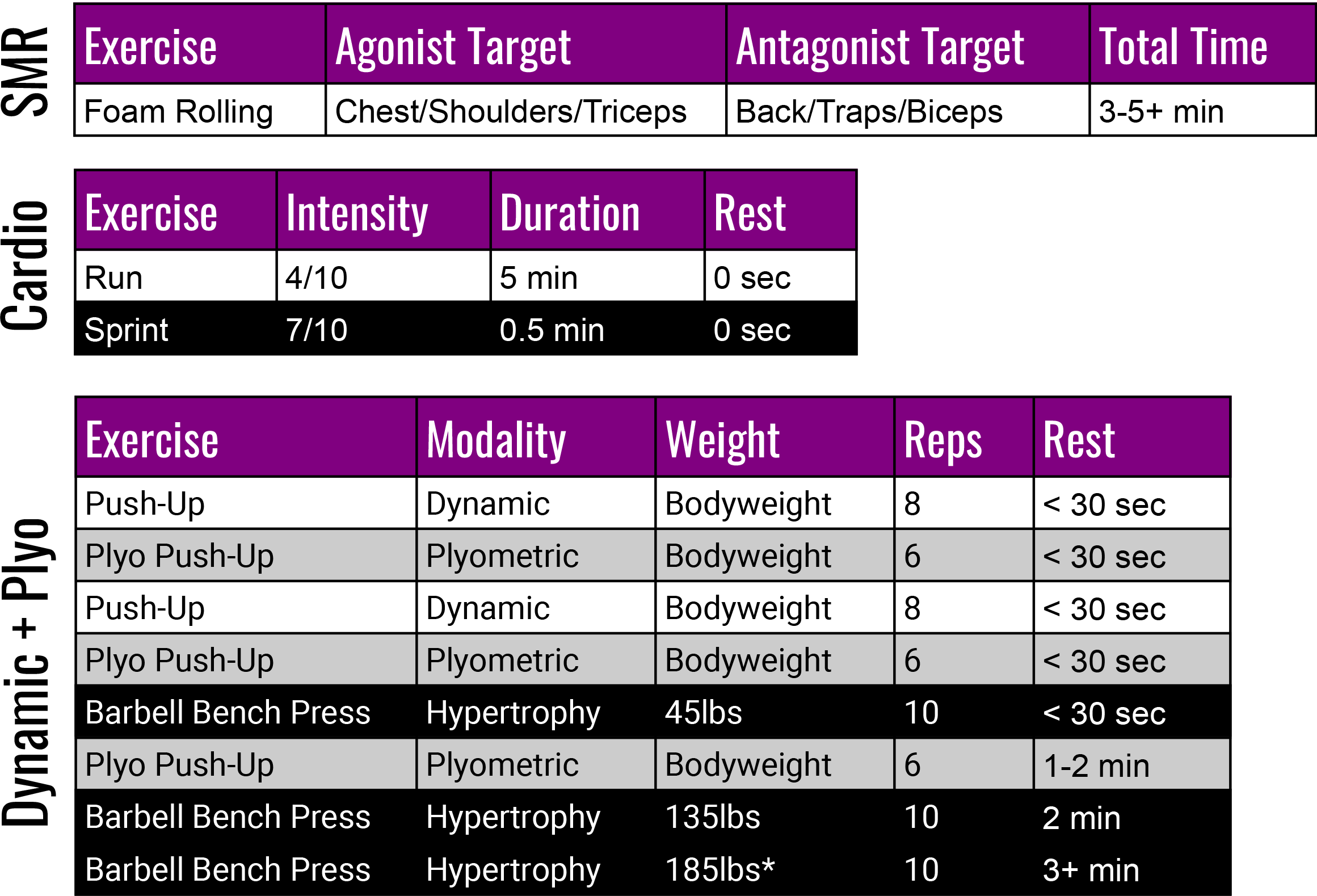

The table above is an example SMR routine that could take place before a day of pressing exercises like bench press or overhead press. The total time is calculated from one 30 second rolling bout per major muscle.

The second part of the general warm up is the cardiovascular portion. This section is designed to warm up the body through a cardio-based activity and lasts 5-6 minutes. Light cardiovascular exercise is a great way to increase blood flow, prepare us mentally for the upcoming session, generate heat, and prime the energy systems we’ll be using later. We get a lot in return for a relatively small expenditure of energy.

Because most resistance training workouts utilize a mixture of fuel sources, we want the general cardio section to utilize our ATP-CP, glycolytic, and aerobic energy systems, while raising body temperature. This can be accomplished by combining an easy aerobic base with a short, high-intensity anaerobic finish. We can passively generate heat and mimic upcoming energy requirements without causing major fatigue. The time you spend in each of these two zones will vary depending on your workout, but about 80-90% should be in an easy to moderate zone with the last 10-20% at a higher intensity.

You’re free to pick whatever modalities you like, but I recommend running and jogging. You like to run? Great. Is cycling more your thing? Go for it. As long as you can adhere to the basic duration and intensity structure, feel free to experiment with different exercise types.

Above is an example cardio structure that can be performed before a session of resistance training. The total time spent on the treadmill is 5.5 minutes. The aerobic section at the beginning increases body temperature and the anaerobic portion activates anaerobic glycolysis and some higher threshold motor units.

In this example scenario, the five aerobic minutes are completed at roughly a 4/10 intensity and the sprint finish is performed at 7+/10. For most people, this is a moderate jog that transitions into a fast run. If you can’t maintain an easy jog during your warm up, don’t stress out about it. However, you need to work towards it. This general outline can be used with different fitness levels and scales to fit any user. On the treadmill, a more fit runner has the ability to crank up both belt speed and incline, while someone less experienced may want to walk at a constant pace and raise the incline to achieve similar energy demands. Do what’s best for you.

The main takeaway here is this general outline can be modified and adapted to your needs. There’s no single, perfect warm up protocol. Lots of different variations can be effective. Feel free to experiment with times, durations, and intensities within the suggested parameters outlined above. If you can boost blood circulation, increase core body temperature, keep it within a 5-8 minute window, and feel energetic afterwards, great.

If you’re in a cold gym or live in a cooler climate, wear a light jacket and/or pants during your warm up to help speed up the heating process and maintain higher body temperatures. You’ve worked hard enough to sweat. Don’t let air conditioning or cooler weather negatively affect your efforts.

Now that we’re warm, sweaty, and ready to exercise, let’s look at the specific warm up portion.

Warm Up Structure: Specific

You can perform the same general warm up before every session, but the specific warm up changes to reflect daily demands. The specific warm up consists of dynamic stretching and plyometric exercises of increasing intensity. This section should take 4-6 minutes to complete.

Dynamic stretching is the first component of the specific warm up. Dynamic stretching is a warm up technique that prepares us for the workload ahead. It does this by introducing moderate loads to muscles, boosting blood flow, increasing joint lubrication, and avoiding fatigue. Dynamic stretches are performed with low-intensity movements and light exercises. These stretches typically use our own bodyweight, safely introduce resistance to our muscles, and take our joints through full ranges of motion. Compound movements that require core activation like push-ups, ring rows, and air squats are great examples. Dynamic stretches should be easy to perform and use a rep pace that’s the same or just barely slower than your normal speed. The exact rep count depends on your experience and ability, but most people should aim to complete 5-10 reps per exercise for 2-3 sets.

Plyometrics are the second component of the specific warm up, and are included to boost the efficiency of neuromuscular activity. These are low-load, high-velocity, power-based exercises that result in quick stretch-shorten cycles of muscles. Plyometrics should be performed with a high (90+%) intensity, light weight, maintain a low rep count (4-6), operate within a 2-3 set total, and not induce fatigue. Similar to dynamic stretching, plyometric movements should ideally incorporate bodyweight exercises like squat jumps, plyo push-ups, kettlebell swings, kipping pull-ups, explosive wall balls, etc. Fast, explosive, and light weight stuff.

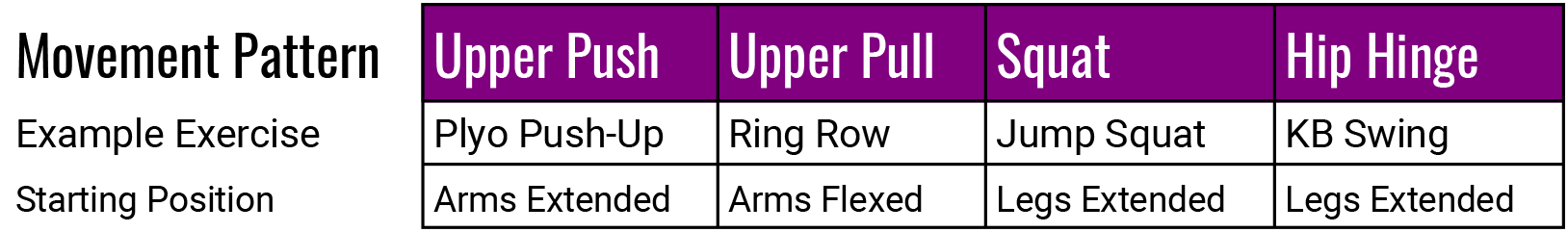

Because a nearly instantaneous stretch-shorten cycle is the primary defining characteristic of plyometrics, all chosen movements should start with the targeted muscles in a contracted/shortened state. For example, an explosive ring row would begin at the top of the row with arms bent. Jump squats begin standing completely upright. Plyo push-ups start at the top with arms extended. Some examples of plyometric exercises for common movement

Without diving too far into the science, performing plyometrics before a workout allows us to utilize post-activation potentiation (PAP). PAP is a theory that basically states our muscles remember how much fiber activation was recently required, and this makes them more likely to recruit at least the same amount of motor units during subsequent, less demanding activities. Post-activation potentiation can result in increased fiber recruitment towards the beginning of a set, greater strength output, and more volume completed under heavy loads.

For example, a max effort squat jump doesn’t load our muscles with a ton of weight, but it does require 100% motor unit recruitment. When performed before a heavy barbell squat, the jumps prime our neuromuscular pathways, create a short-term contractile history, and make the motor neurons involved easily excitable due to their recent activation. Performing one exercise that mimics the motor unit recruitment requirements of another essentially lowers motor unit thresholds by decreasing the stimulation needed to create action potentials. Post-activation potentiation is what makes moderate weight feel unexpectedly light when performed after a heavy set.

Studies have shown that this muscular response works with both high-speed, low-resistance (plyo push-up to improve bench press) and low-speed, high-resistance (heavy squat to improve sprint time) efforts. More research needs to be done on PAP to fully understand it but enough studies suggest it’s too effective to ignore.

The final phase of the specific warm up is the transition into the actual workout.

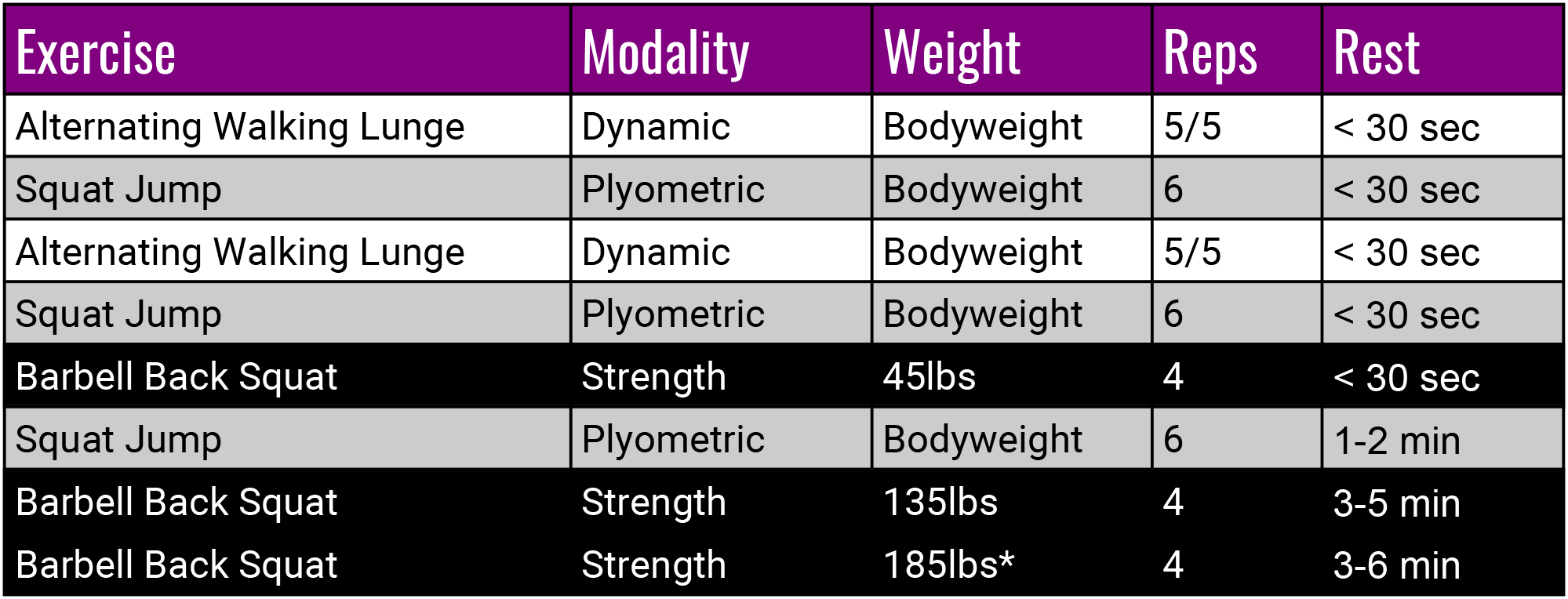

As we gradually progress through dynamic stretching and plyometrics, we can incorporate increasingly heavier sets of the starting exercise until we reach our first working set. The example below highlights one way to lead up to a day of squatting.

As seen in the table above, the session begins with dynamic stretching in the form of walking lunges, adds in squat jump plyometrics, then phases out stretching and plyo activities as the barbell work is incorporated. Rest time is kept to a minimum until heavier working loads are reached. Dynamic stretching and plyometric work are performed for 2-3 sets each. The final exercise on the list is the first working set of the day.

Let’s put both sections together and look at two full warm up examples.

Complete Warm Up Examples

The example below is designed to work with a hypertrophy or strength focused pressing workout that leads up to bench press. The general and specific sections are combined.

This warm up heats up the body, activates energy systems, primes neuromuscular pathways, and introduces resistance to our chest, shoulders, and triceps. All of this leads to the first set of bench press. Reps for regular push-ups and plyo push-ups are kept far from failure. The first bench press working set starts with six reps of 185 lbs, so the weight increases based on that end goal. Keep the rep counts of your ramping loads roughly the same as the first working set.

The loads of your first working sets will require their own unique ramping speeds. All working sets need to be progressively introduced as you transition from exercise to exercise. This means that you should perform some type of warm up or ramping load progression when you start a new exercise during your workout. For example, after finishing bench press, don’t immediately start your first working set on overhead press. You don’t need to perform the full warm up routine again, but 1-2 sets of plyometrics staggered between 1-2 ramping loads is recommended. This is much more important when transitioning from one muscle group to another, like moving from chest to back.

Because pre-exercise prep is not limited to resistance training, let’s switch gears and look at a running warm up.

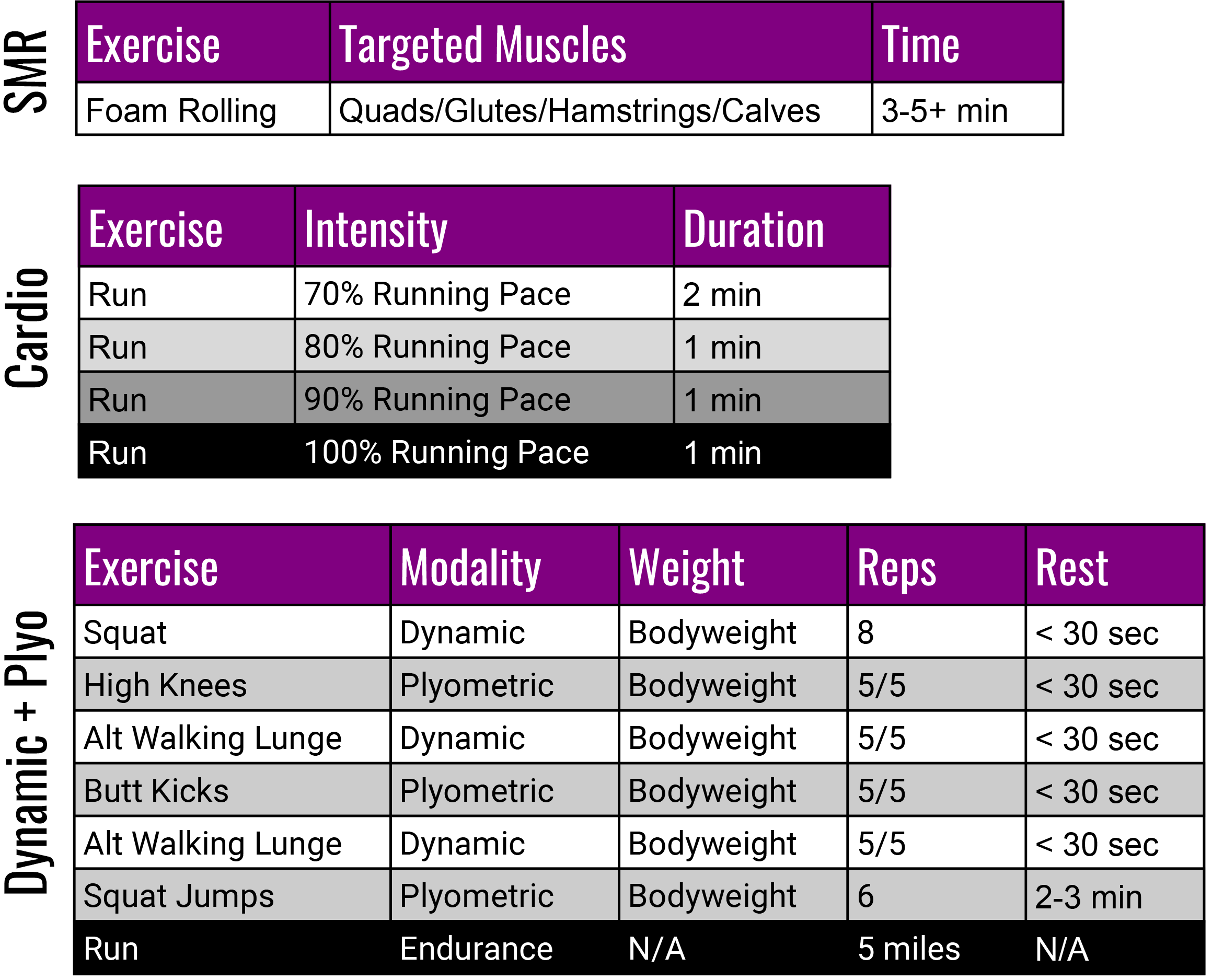

The general warm up starts by rolling out our lower limbs then slowly takes us from an easy jog to our normal running pace over the course of five minutes. This aerobic progression should increase our metabolic efficiency of fats and make the session easier. This pre-run routine does not contain any anaerobic cardio because the long run doesn’t include sprinting or high-intensity exercise. However, a quick anaerobic finish shouldn’t negatively affect the run if time is dialed in correctly.

The specific warm up follows the same formula as the bench press example, and contains minimally fatiguing dynamic and plyo-based exercises. The muscular demands of cardiovascular exercise aren’t the same as resistance training, but we still want our muscles to be warm. Unlike the bench press example, this outline doesn’t have a first working set to ramp up to. Instead, we rest for a few minutes after completing all dynamic and plyometric movements before starting the run.

We could spend all day covering every possible workout scenario and the different warm ups that accompany them, but I’m going to stop with these two. The framework provided in this chapter should allow you to easily build your own. Don’t overthink it.

Static Stretching?

I don’t recommend any static stretching before or during a workout.

Although there is conflicting research regarding the effectiveness and safety of static stretching prior to exercise, there are too many studies that show a negative effect on performance. If you’re so tight that foam rolling and dynamic warm up exercises have little to no impact on your range of motion, it may be best to shift your fitness priorities for that day. Consider taking some time off to work on mobility and recovery.

However, if your current warm up routine does include some static stretching, don’t cut it out immediately. Dropping it all at once might screw with your pre-session confidence. Slowly phase it out over the course of a few weeks. Reduce the duration of each stretch by a few seconds each time it’s performed until you reach zero. But if absolutely no convincing will change your mind about warm up static stretching and you have to do it to feel fully prepared for a session, cap each segment duration at 10-15 seconds and stay away from pain or any muscular discomfort. Stretching for less than 30 seconds shouldn’t have a negative impact on exercise performance.

Static stretching is an important part of any good routine, but needs to be implemented at the right time.

Final Thoughts

You might be thinking that this was a complicated way to say you should do cardio and some light exercises before a workout. You’re probably right. But at least now you know how an effective warm up contributes to exercise performance, have an outline to help you design your own, and may have learned something new along the way.

Foam roll. Cardio. Dynamic stretching. Plyometrics. Workout. Pretty easy, right?

Experiment by manipulating different variables. Find what works best for you. Share what you discover. Have fun.

References

Baechle, T. R., & Earle, R. W. (2008). Essentials of strength training and conditioning. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Baxter, C., Naughton, L. R., Sparks, A., Norton, L., & Bentley, D. (2016). Impact of stretching on the performance and injury risk of long-distance runners. Research in Sports Medicine, 25(1), 78-90.

Beardsley, C., & Škarabot, J. (2015). Effects of self-myofascial release: A systematic review. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 19(4), 747–758.

Behrens, M., Mau-Moeller, A., Mueller, K., Heise, S., Gube, M., Beuster, N., … Bruhn, S. (2016). Plyometric training improves voluntary activation and strength during isometric, concentric and eccentric contractions. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 19(2), 170–176.

Bishop, David John. (2003). Warm Up I: Potential Mechanisms and the Effects of Passive Warm Up on Exercise Performance. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.). 33. 439-54.

Bradbury-Squires, D. J., Noftall, J. C., Sullivan, K. M., Behm, D. G., Power, K. E., & Button, D. C. (2015). Roller-massager application to the quadriceps and knee-joint range of motion and neuromuscular efficiency during a lunge. Journal of athletic training, 50(2), 133-40.

Brunner-Ziegler, S., Strasser, B., & Haber, P. (2011). Comparison of Metabolic and Biomechanic Responses to Active vs. Passive Warm-up Procedures before Physical Exercise. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 25(4), 909–914.

Chaouachi, A., Castagna, C., Chtara, M., Brughelli, M., Turki, O., Galy, O., … Behm, D. G. (2010). Effect of Warm-Ups Involving Static or Dynamic Stretching on Agility, Sprinting, and Jumping Performance in Trained Individuals. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(8), 2001–2011.

Cheatham, S.W., Kolber, M.J., Cain, M., & Lee, M.C. (2015). The Effects of Self-myofascial Release Using a Foam Roll or Roller Massager on Joint Range of Motion, Muscle Recovery, and Performance: a Systematic Review. International journal of sports physical therapy, 10 6, 827-38.

CRAMER, J. T., HOUSH, T. J., JOHNSON, G. O., MILLER, J. M., COBURN, J. W., & BECK, T. W. (2004). ACUTE EFFECTS OF STATIC STRETCHING ON PEAK TORQUE IN WOMEN. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 18(2), 236–241.

Davies, G., Riemann, B. L., & Manske, R. (2015). CURRENT CONCEPTS OF PLYOMETRIC EXERCISE. International journal of sports physical therapy, 10(6), 760-86.

Harwood, B., & Rice, C. L. (2012). Changes in motor unit recruitment thresholds of the human anconeus muscle during torque development preceding shortening elbow extensions. Journal of Neurophysiology, 107(10), 2876–2884.

Jankowski, C. M. (2008). Dynamic Warm-Up Protocols, With and Without a Weighted Vest, and Fitness Performance in High School Female Athletes. Yearbook of Sports Medicine, 2008, 74–75.

KAY, A. D., & BLAZEVICH, A. J. (2012). Effect of Acute Static Stretch on Maximal Muscle Performance. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 44(1), 154–164.

Lorenz D. (2011). Postactivation potentiation: an introduction. International journal of sports physical therapy, 6(3), 234-40.

Macgregor, L. J., Fairweather, M. M., Bennett, R. M., & Hunter, A. M. (2018). The Effect of Foam Rolling for Three Consecutive Days on Muscular Efficiency and Range of Motion. Sports medicine – open, 4(1), 26.

McGowan, C. J., Pyne, D. B., Thompson, K. G., & Rattray, B. (2015). Warm-Up Strategies for Sport and Exercise: Mechanisms and Applications. Sports Medicine, 45(11), 1523–1546.

Miranda, H., Maia, M. de F., Paz, G. A., & Costa, P. B. (2015). Acute Effects of Antagonist Static Stretching in the Inter-Set Rest Period on Repetition Performance and Muscle Activation. Research in Sports Medicine, 23(1), 37–50.

McCrary JM, Ackermann BJ, Halaki M A systematic review of the effects of upper body warm-up on performance and injury Br J Sports Med 2015;49:935-942.

Monteiro, E. R., & Neto, V. G. (2016). EFFECT OF DIFFERENT FOAM ROLLING VOLUMES ON KNEE EXTENSION FATIGUE. International journal of sports physical therapy, 11(7), 1076-1081.

NAKAMURA, K., KODAMA, T., & SUZUKI, S. (2012). Effects of Active Individual Muscle Stretching on Muscle Function. Rigakuryoho Kagaku, 27(6), 687–691.

Page, P. (2012). CURRENT CONCEPTS IN MUSCLE STRETCHING FOR EXERCISE AND REHABILITATION. Int J Sports Phys Ther., 7(1), 109-119.

Park, H. K., Jung, M. K., Park, E., Lee, C. Y., Jee, Y. S., Eun, D., Cha, J. Y., … Yoo, J. (2018). The effect of warm-ups with stretching on the isokinetic moments of collegiate men. Journal of exercise rehabilitation, 14(1), 78-82. doi:10.12965/jer.1835210.605

Piazzesi, G., Reconditi, M., Linari, M., Lucii, L., Bianco, P., Brunello, E., … Lombardi, V. (2007). Skeletal Muscle Performance Determined by Modulation of Number of Myosin Motors Rather Than Motor Force or Stroke Size. Cell, 131(4), 784–795.

Schoenfeld, B. (2017, August 20). Warming Up Prior to Resistance Training: An Excerpt from “Strong & Sculpted”. Retrieved from https://www.lookgreatnaked.com/blog/warming-up-prior-to-resistance-training-an-excerpt-from-strong-sculpted/

Schroeder, A. N., & Best, T. M. (2015). Is Self Myofascial Release an Effective Preexercise and Recovery Strategy? A Literature Review. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 14(3), 200–208.

Sim, Y.-J., Byun, Y.-H., & Yoo, J. (2015). Comparison of isokinetic muscle strength and muscle power by types of warm-up. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 27(5), 1491–1494.

Slimani, M., Chamari, K., Miarka, B., Del Vecchio, F. B., & Chéour, F. (2016). Effects of Plyometric Training on Physical Fitness in Team Sport Athletes: A Systematic Review. Journal of human kinetics, 53, 231–247.

Smith, C. A. (1994). The Warm-Up Procedure: To Stretch or Not to Stretch. A Brief Review. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 19(1), 12–17.

Su, H., Chang, N.-J., Wu, W.-L., Guo, L.-Y., & Chu, I.-H. (2017). Acute Effects of Foam Rolling, Static Stretching, and Dynamic Stretching During Warm-ups on Muscular Flexibility and Strength in Young Adults. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, 26(6), 469–477.

Sullivan, K. M., Silvey, D. B., Button, D. C., & Behm, D. G. (2013). Roller-massager application to the hamstrings increases sit-and-reach range of motion within five to ten seconds without performance impairments. International journal of sports physical therapy, 8(3), 228-36.

Tamer T. M. (2013). Hyaluronan and synovial joint: function, distribution and healing. Interdisciplinary toxicology, 6(3), 111-25.

Thorborg, K., Krommes, K. K., Esteve, E., Clausen, M. B., Bartels, E. M., & Rathleff, M. S. (2017). Effect of specific exercise-based football injury prevention programmes on the overall injury rate in football: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the FIFA 11 and 11+ programmes. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51(7), 562–571.