Nutrition Basics

The following content is taken from chapter two of Fitness & Nutrition Programming for Beginners, Nutrition: Fueling for Fitness. This section covers how often to eat, includes a suggested macronutrient split, and provides examples of certain foods that can fit the overall plan. The strategy outlined below is designed to help beginners build a sustainable diet that promotes recovery and performance. Take what’s included as a guide and build what’s best for you.

Meal Timing, Macronutrient Intake Quantities, & Food Sources

We can’t all follow the same diet and expect identical results. Total daily calories and meal compositions need to reflect our individual goals, lifestyles, and genetic differences. Effective nutrition plans must be tailored to the specific needs of the user, and this custom approach inevitably results in a wide range of dietary variation from person to person. Luckily, all good diets share a common outline that’s healthy, sustainable, and simple.

This section covers a realistic meal frequency strategy, how to estimate total daily energy expenditure (TDEE), recommended ranges of macronutrient intake quantities, and some whole food sources of carbohydrates, protein, and fats.

To start things off, let’s talk about meal timing.

While it might not seem like the most important factor to fitness success, eating frequency matters. The timing of carbohydrate and protein rich meals can affect energy availability, muscle growth, recovery, weight loss progress, and the regulation of many internal functions. An easy to follow eating schedule also gives our diet consistency and predictability, allowing new routines to become habits. By eating at predetermined times, rather than impulsively and in response to hunger, long-term diet adherence is easier and general program satisfaction is higher.

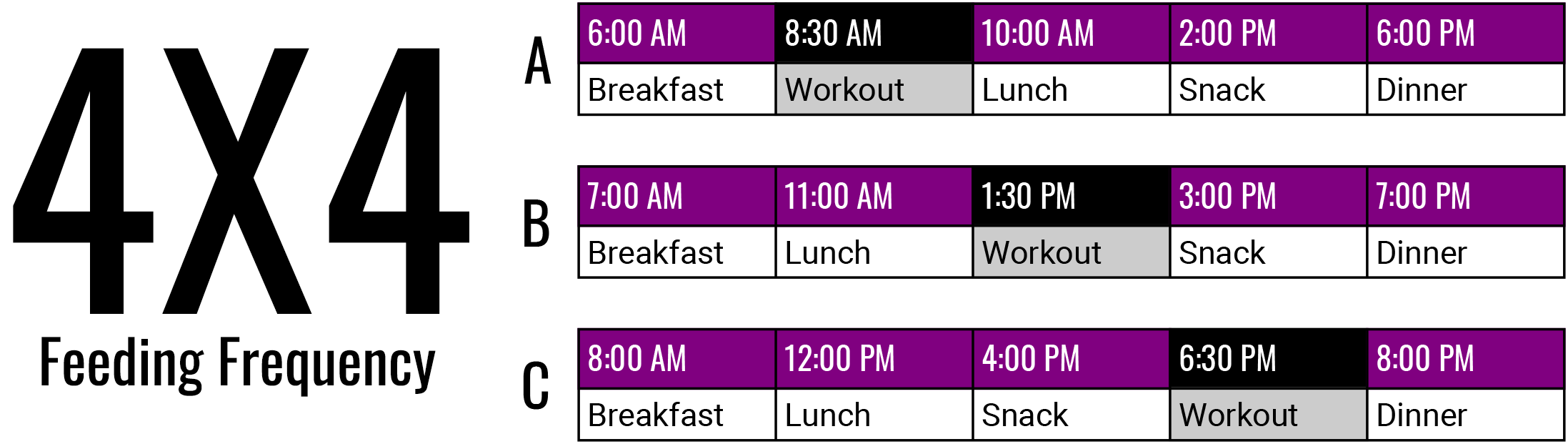

I recommend most people consume four meals per day, each separated by four hours. This results in 12 hours of feeding and 12 hours of fasting daily. Some example schedules are listed below. This suggested routine can fit into nearly any schedule as it essentially breaks down into a breakfast/lunch/snack/dinner split. At least three of these meals should come from whole food sources, not shakes or bars.

Our four empty plates are ready to go. How much food should each contain?

As covered earlier, our total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) represents all of the calories we burn per day, while energy intake (EI) is the total number of daily calories we consume. Calories in versus calories out is ultimately what determines changes in weight, so our total daily intake should reflect our daily expenditure. This means that before we can discuss which foods help us gain muscle or lose fat, we need to calculate TDEE and establish energy balance.

Total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) can be estimated in two easy steps.

- Keep a detailed record of your normal diet for at least one week by using a free calorie tracking app (Lose It, Cronometer, MyFitnessPal, etc) and reading food labels. During this seven day period, refrain from making major changes to your diet. Record absolutely everything you put in your body. At the end of each day, look back over your eating habits and take note of the caloric totals along with the macronutrient contents of each meal. Are you eating more or less than you thought? Are certain macronutrients dominating your diet while others are nearly absent? This number can help explain any recent changes in body composition and/or energy levels.

- Estimate your total daily expenditure by using a simple online TDEE calculator. For the most accurate number, have your body fat percentage measured at a local gym or university. How does your estimated TDEE compare to the seven day tracking average? If this calculated TDEE is lower than your tracked intake average and weight gain is an issue for you, this difference could explain the problem. If you have a pedometer, use it. Keep track of your step count throughout the day and use this activity data to help form your TDEE estimation.

By combining these two data points with what you intuitively know about your dietary needs and the way your body responds to certain meal sizes, you should be able to narrow down your TDEE to a reasonably narrow intake window that can be further refined over time. It will require a little experimentation to dial in energy balance intake correctly, but this discovery process shouldn’t take too long if you pay attention to what you eat and how those dietary habits make you look and feel. It’s important to note that neither one of these two TDEE calculation methods are perfectly accurate on their own. They’re only estimations. If your gym offers metabolic testing and can provide you with an accurate assessment of your BMR, take advantage of it. The more information you can gather, the better.

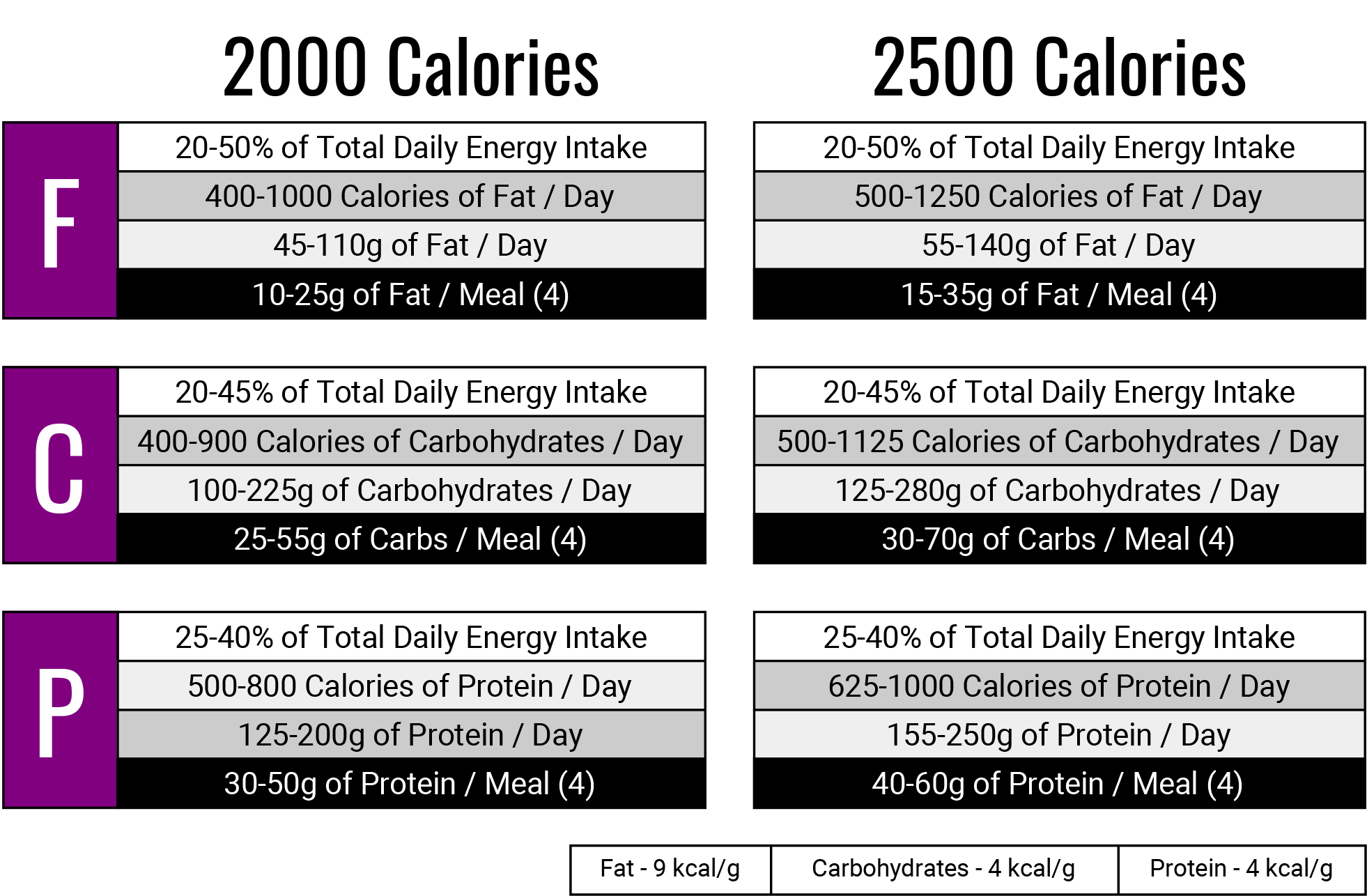

Now that we know how to calculate our intake requirements for energy balance, let’s discuss the composition of those calories from a macronutrient perspective. The table on the next page contains my recommended intake ranges for each macronutrient. 2000 and 2500 total daily calorie versions are listed as examples. These examples illustrate how caloric totals affect macronutrient quantities, both on a per day and per meal basis.

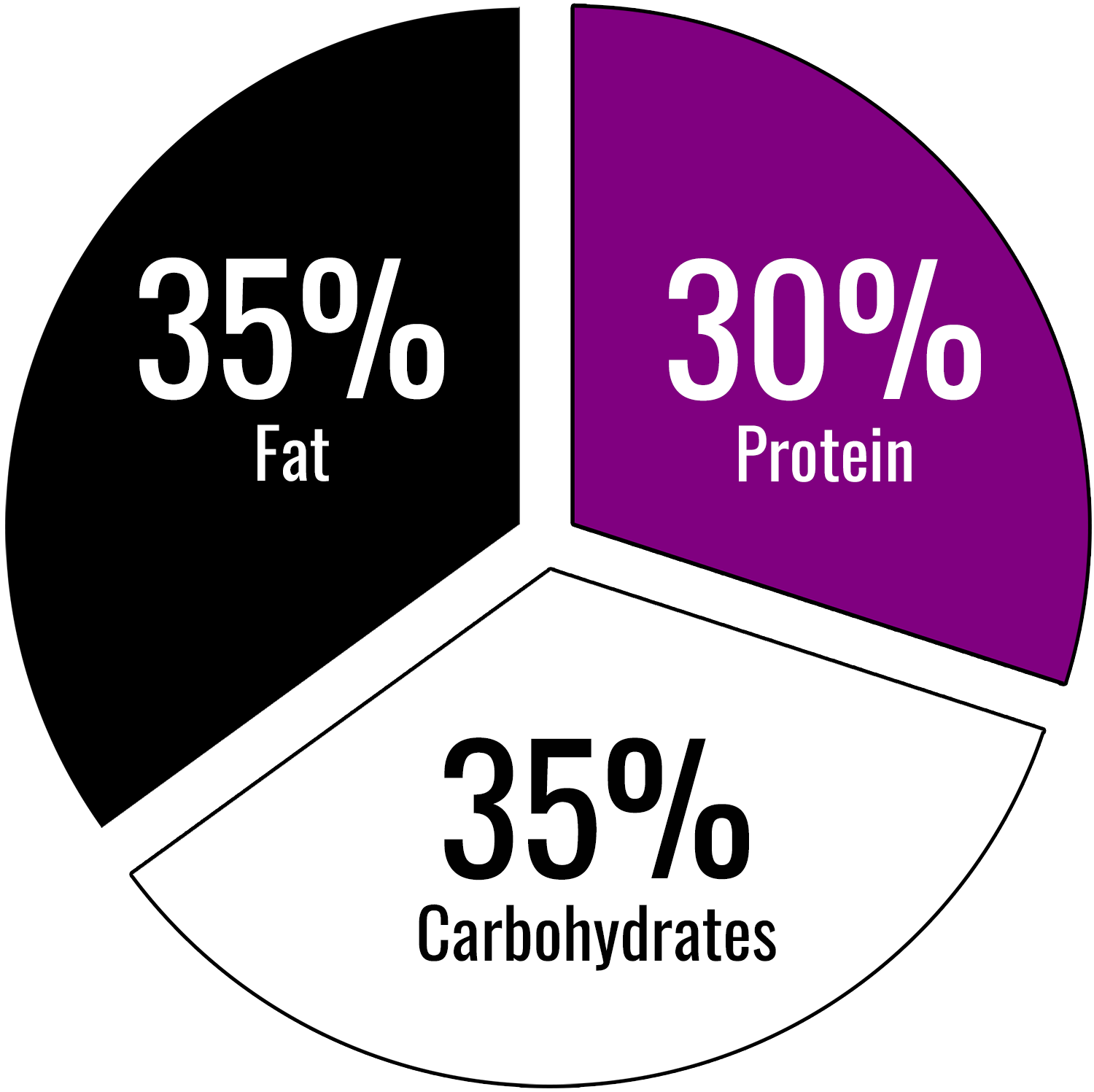

As seen above, each macronutrient is associated with a recommended intake range. 25-40% of the 2000 calorie daily total should come from protein, 20-45% from carbohydrates, and 20-50% from fat. Notice that none of these ranges include a 0% intake option. All three macros should be present in significant quantities. A 30% protein, 35% carbohydrate, and 35% fat split is my recommended starting point if you have no idea where to begin. However, there are many different viable macronutrient intake combination possibilities, so feel free to experiment with your meal compositions to find what works best for you.

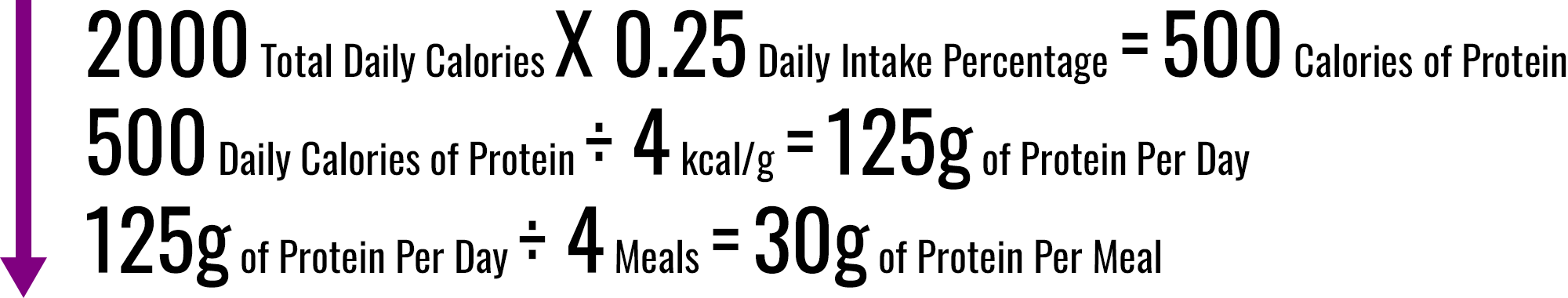

These caloric percentages can be converted into grams of food to make meal preparation and tracking easier. The gram (g) is our unit of measurement for macronutrient intake quantities. Let’s use the low end of protein intake (25%) as an example of this conversion process.

25% of 2000 calories is 500 calories (2000 x 0.25 = 500) of protein. Those 500 total daily protein calories are then divided by 4 kcal/g (energy density of protein) to determine their weight in grams. 500 calories divided by 4 kcal/g equals 125g of protein per day. We then divide 125g of protein by four to evenly distribute daily protein content across each of our four meals. 125g of total daily protein divided by four meals equals roughly 30g of protein per meal.

This conversion process can be used to calculate the intake quantities of all three macronutrients. Be sure to remember the specific energy densities of protein (4 kcal/g), carbohydrates (4 kcal/g), and fat (9 kcal/g) when converting units.

If you enjoy maximizing exercise performance and tracking fitness progress, you’ll likely find the process of macronutrient intake experimentation enjoyable. Discovering your unique meal composition sweet spot is a satisfying feeling. However, if a majority of the content in this chapter is new to you and the subject of nutrition is a relatively foreign topic, it’s not necessary to obsess over the intake information listed above.

Food should be fun and a source of joy during preparation and consumption. If we fixate on the macronutrient percentages of everything we eat, we’ll inevitably develop an unhealthy relationship with food. Use my suggested intake ranges and your newly acquired calories-to-grams conversion skills to help shape your diet, but don’t let either of these things control you. Try to be aware of what you eat, do your best to make smart choices, and keep working towards your goals. Aim for structure and consistency, not perfection.

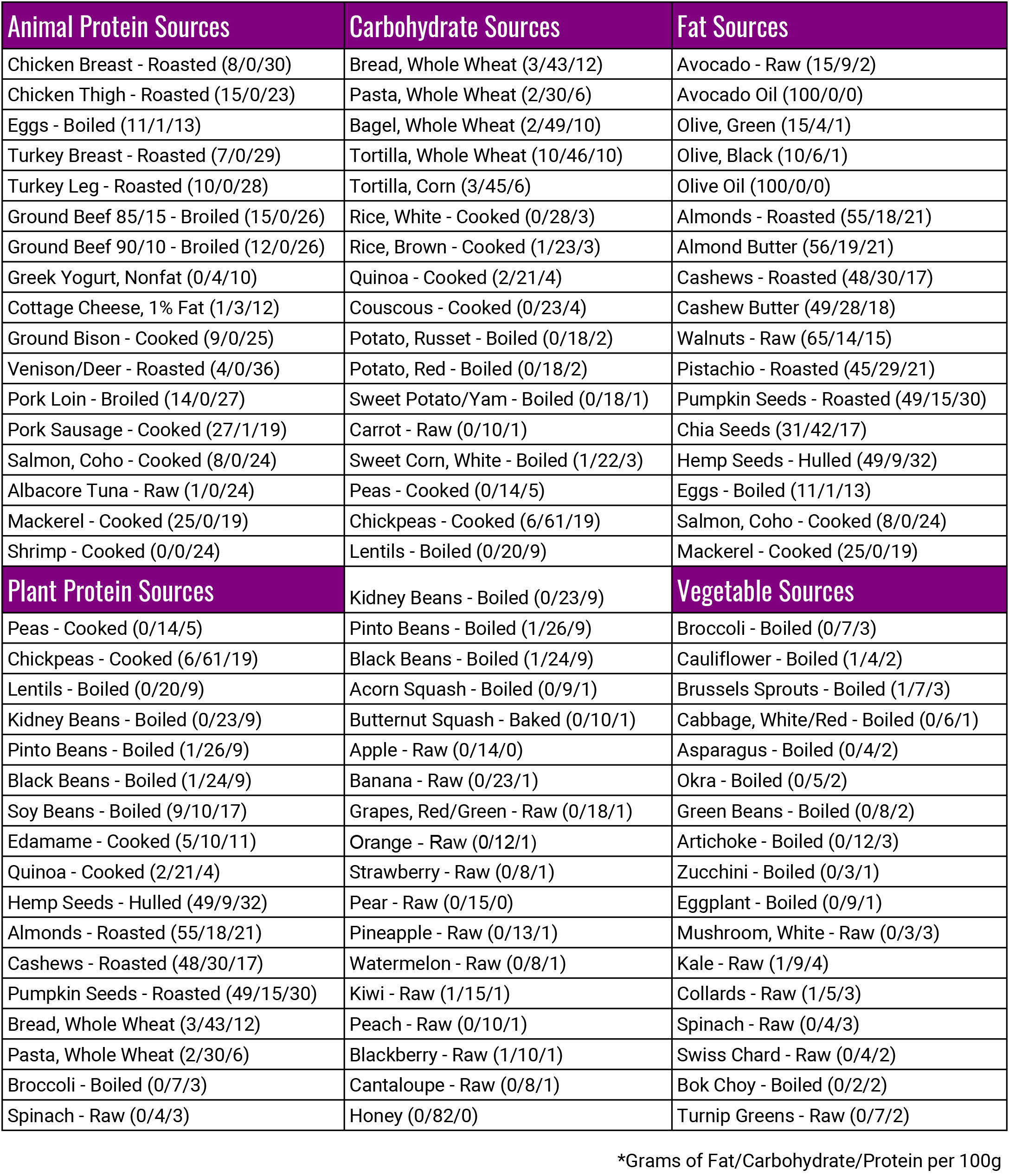

To help make smart choices a bit easier, the table on the next page contains some foods from each macronutrient category. Vegetable/fiber sources are included. This is not a comprehensive list of suggested foods to eat.

Notice that most foods listed contain a mixed macronutrient profile and only a handful of items consist solely of protein, carbohydrates, or fat. It’s important to be mindful of nutrient composition differences as you plan out your meals.

For example, 100g of chickpeas contain 6g of fat, 61g of carbohydrates, and 19g of protein. Chickpeas are a great source of protein but this food’s nutrient profile can lead to excessive carbohydrate intake if that particular macronutrient is not accounted for. Most foods also vary widely in the composition of their macronutrient subcomponents. Almonds and walnuts both are great sources of fat, but they contain very different levels of mono and polyunsaturated fats. Use your tracking app and read food labels to know what you’re eating.

Along with protein, carbohydrates, and fats, the table also includes a list of non-starchy and leafy green vegetables. I recommend that 1-2 of your daily meals include healthy portion sizes of items from that list. A fiber-rich vegetable source at lunch and at dinner easily accomplishes this. Track these foods.

With so many different foods to choose from and macronutrient intake ranges to work with, there are endless combination possibilities for your diet. If you’re feeling a little overwhelmed by the thought of using the information in this section to completely restructure your diet, that’s normal. It’s a lot to take in. Limitless variety is great for some, but it can be mentally paralyzing for others. Most lifestyle changes need to be easy to implement or they’ll never last long enough to become long-term habits. Let’s take the key points from this section and condense them down into a simple, step-by-step plan.

- Start tracking your current diet with a calorie tracking app and by reading food labels. If you put it in your body, count it.

- Compare one week of your normal eating habits with my recommendations and note the differences between the two. Assess which factors will be easy to fix and those that will take more discipline. If you don’t know what intake ranges to aim for, start with a 30% protein, 35% carbohydrate, and 35% fat split. Try to consume at least 30g of protein per meal.

- Over the course of a few days or weeks, gradually restructure your meals until their contents and timings fall in line with my suggestions. For example, is your protein intake a little low? If so, slightly increase your portion size per meal. Focus on a transition process that occurs along a realistic timeline and promotes long-term program adherence.

- When you finally hit your intake goals and are able to meet them consistently, assess your energy levels and exercise performance. Do you feel mentally sharp and energetic, or have these recent changes resulted in fatigue, mental fog, and/or undesirable changes in body composition? If you don’t feel amazing, play with your food options and intake percentages. Experimentation is essential here.

- Keep tracking your food and trying new things. Use this documentation process to truly learn the macronutrient contents of your meals. Calorie counting apps are incredibly useful because they teach us about our habits, but we do not want to manually track intake forever. Teach your eyes to accurately identify what you’re consuming.

- When you feel confident that everything’s dialed in for energy balance, start playing with a slight deficit for weight loss or a surplus for weight gain. Building muscle and losing fat will be simple because you took the time to understand your individual dietary needs.

Some will find the process of TDEE calculation and meal remodeling to be easy and straightforward. If you’re currently mindful of what you eat, transitioning to something slightly more structured won’t be too difficult. However, this won’t be the case for everyone. Nutrition can be a difficult subject to understand and breaking bad dietary habits is even harder. If your relationship with food has historically been more problematic than beneficial and you’ve felt discouraged by a lack of progress, focus on the little victories moving forward. Take your time as you form new habits. It’s not a race.

With energy balance requirements calculated and new healthy eating habits formed, our dietary foundation is built. We now know what, when, and how much to eat because we took the time and put in the effort necessary to discover what our body needs. This equilibrium between intake and expenditure is a great place to start a fitness journey, but it can also be an acceptable endpoint for many different training goals. A diet that focuses on energy balance can be a fantastic nutritional strategy to gradually lose fat and build lean tissue at the same time. However, ambitious fat loss and muscle growth goals require more aggressive strategies.

Fasting & Fat Loss

I don’t recommend regularly occurring, extended periods of fasting for most people.

However, moderate fasting strategies can be effective for heavier individuals looking to safely expedite their fat loss progress.

If you’re interested in fasting beyond 12 hours daily, consider modifying the 4X4 outline to 3X4 and implementing a 16:8 (Hours Fasting : Hours Feeding) fasting routine. This results in three meals per day, each separated by four hours, with 16 hours of fasting. Pay close attention to any changes in exercise performance or mood/energy levels during this time. Modify your eating windows to fit what’s best for you. I personally like to begin my fast 3-5 hours before bed.